Marthe Armitage began printing linocut wallpaper in the 1960's with three babies at home. She was inspired to make her first design, "Angelica," while pushing a stroller along the Chiswick riverbank.

"Angelica"

"Gardeners" installed in Marthe's sitting room, along with a lamp designed by her late husband, featuring "Solomon's Seal" on the shade. A new version of this lamp is being produced by her grandson Joe. Both photos of Marthe's home from Bible of British Taste.

Now in her mid-80's, Marthe still prints her wallpapers herself with the help of her daughter Joanna Broadhurst. They are available through Hamilton Weston Wallpapers & Design and made to order with your own color specifications, though her preference is for soft greens, blues, dull blacks and ochres.

One of two linocut blocks for "Chestnut."

"Chestnut" on the press.

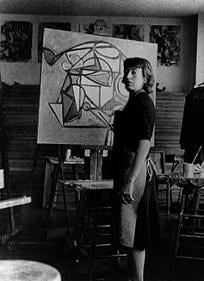

Marthe hand printing "Chestnut" the sore back way.

A bathroom in Dinder House with "Chestnut" installed.

Martha on her staircase. Then a lucky little girl's bedroom with the same wallpaper, in blue, picked out by her mom, Miranda Brooks.

A wonderful short film, Back to the Drawing Board, by Sue Haycock in which Marthe explains how to design for repeat and the virtues of doing so on paper.