I just polished off my take away stash of Omotesando Koffee beans this morning. Grumpy-nostalgic. When we were in Tokyo this September, Lili and I had the startling good fortune to stay in an Airbnb dynamic directly around the corner from this jewel which, dispite the aroma, took us days to notice because we were so distracted by the grass field across the way. The coffee was superb, as was the one perfect snack—baked custard cubes. Missing Tokyo jewels and hot coffee on a hot day.

Kathleen Whitaker x G&G Boob Earrings

Solid 14k gold Boob Earrings, inspired by “Boobs”, made in Los Angeles by Kathleen Whitaker. BUY

This shot, with the amazing—accidental?—boob trinity if you count the upper arm nipple is a collaboration between me, Kathleen’s earring, and a self-portrait included in Self-Exposures: A Workbook in Photographic Self-Portraiture by Naomi Weissman & Debra Haimerdinger (1979).

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

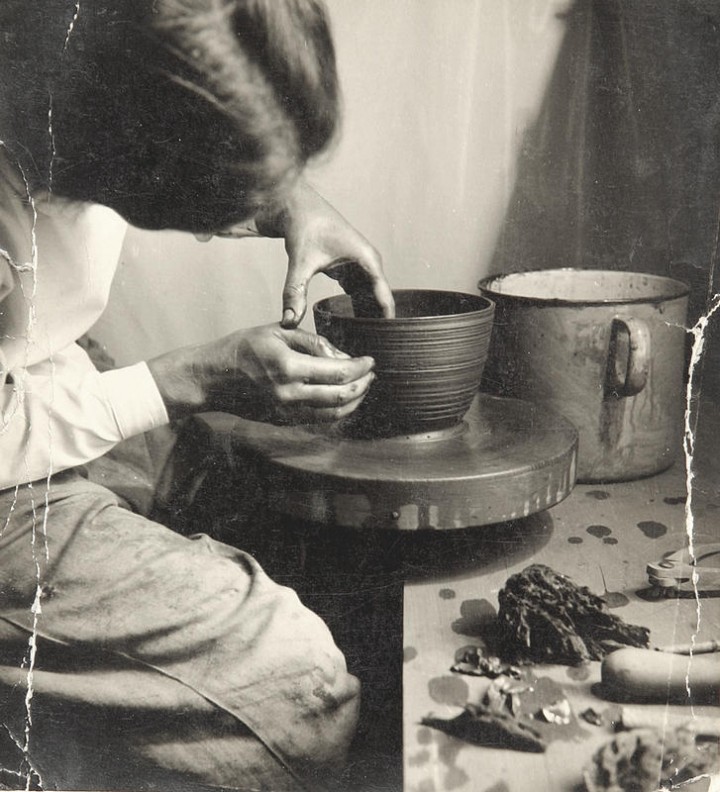

Lucie Rie Working

Lord Snowdon’s photograph of Lucie’s hands and Sam Haskin’s portrait of Lucie taken around 1990.

Lucie Rie and Hans Coper pottery upstairs at 18 Albion Mews in 1950. Then Lucie sunbathing in the 1960s. Photo by Stella Snead. Then her pink porcelain conical bowl, c. 1978.

Lucie, around 1935, in her Vienna studio. Then a shot of her London studio with her glazing materials.

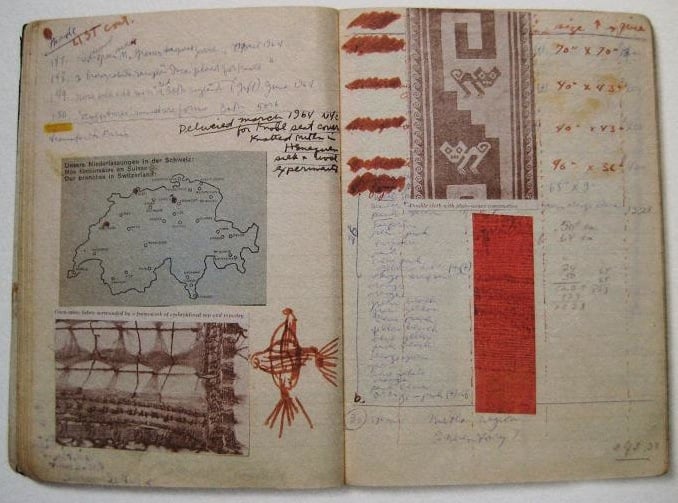

Lucie in her London studio. Photo by Hansi Böhm. Then a page from her Vienna-days glazing notebook, 1920s.

A busy schedule filling orders in 1946 and Lucie getting it done in her London studio.

The group of vases were on display at London’s Berkeley Gallery, 1962. Photo by Jane Gate. Then Lucie potting in the 1980s.

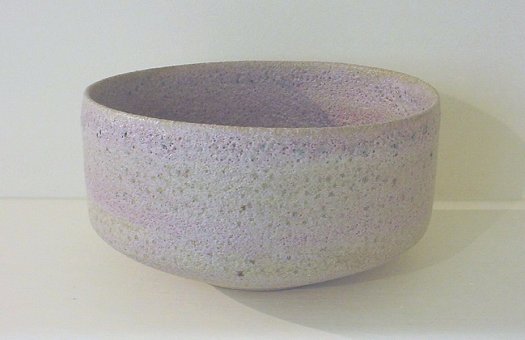

Volcanic bowl with manganese border, c. 1986, then stoneware bowl with volcanic glaze, 1990 (from last firing), then yellow porcelain bowl, 1967, then turquoise bowl with bronze rim, 1983. These images from Galerie Besson.

Lucie Rie at her front door, photo by Jim Hair. ThenLucie’s pots arranged on the Plischke shelves at Albion Mews, 1950.

Lucie Rie was born on March 6, 1902 to a prominent family in Vienna. In 1922 she entered the Kunstgewerbeschule, a school of arts and crafts associated with the Wiener Werkstätte, where she was, she said, instantly ‘”lost” to the potter’s wheel. She developed quickly, combining a taste for a clean, modernist aesthetic with daring technical skill.

In 1926, she married and commissioned an apartment from a young Viennese architect, Ernst Plischke, on Andreasgasse. Lucie had purchased a chair from Plischke and like it so much that she asked him to furnish her entire apartment. It was his first commission. Plischke designed every detail of the flat to suit the young potter, including studio space with a gas-fired kiln and, in the living room, walnut cupboards with versatile shelves that could be rearranged to display her work. When Lucie fled to London in 1938, she had the entire interior shipped over and re-erected in a mews house in Bayswater, where she lived and worked, to great renown, for the next 50 years. After she passed, the studio was moved and reconstructed again, this time in the Victoria and Albert Museum‘s ceramics gallery.

Lucie is often described as steely and too rigorous to be a good teacher, though she had a lasting mentorship turned creative partnership with Hans Coper and always made time to meet with anyone with a serious interest in pottery. Those who qualified for her time were invited over to her studio for tea, cake, and serious conversation, so long as it wasn’t technical talk about pottery.

Read more about this great dame on the VADS essay site set up for her in a nice timeline format and with lots more great images. The best spot to check out images of her work is through Galerie Besson, which represented her.

Pouring bowl, c.1952 and another portrait of Dame Lucie by Snowdon.

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

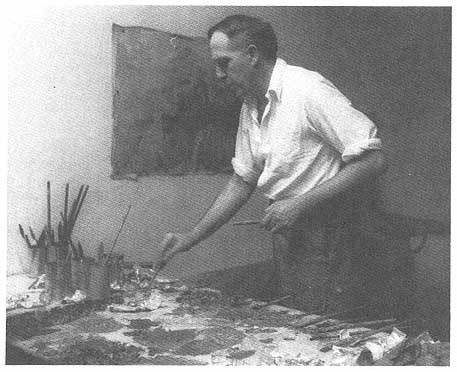

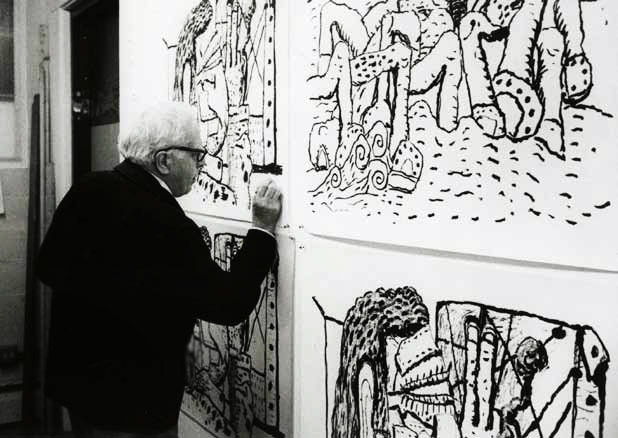

Philip Guston Working

Dickens in the studio, then a portrait of Philip Guston in 1929. Photo by Leonard Stark. And The Studio, 1969.

Guston in 1942, painting celestial navigation murals for the Navy. And, in 1957, painting in his loft on 18th Street, New York City. Photo by Arthur Swoger.

Two shots of Guston’s studio by Denise Hare, then The Painter’s Table, 1973.

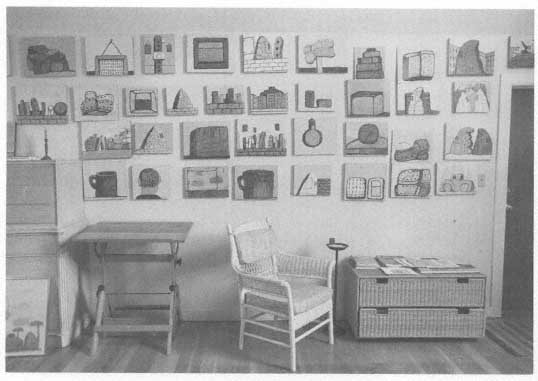

A wall in Guston’s Woodstock studio showing several paintings from 1968. Photo by Denise Hare. And The Rest Is For You, 1973.

More great studio shots by Denise Hare.

The Canvas, 1973, then a shot of Guston’s studio by Denise Hare, then Painting, Smoking, Eating, 1973, then another shot by Denise Hale of Guston in the studio.

A solid many of these images were published in A Critical Study of Philip Guston by Dore Ashton. I’ve read it and it’s a great beginning! You can read it online and check out some more images here.

Looking forward to lots more on Guston from Drummer Neal Morgan TOMORROW NIGHT. See ya then. Also, it’s not so much worky, more like the ultimate dream of leisure, but who can resist—

Roma (Fountain), 1971

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Follow This

Laura Owens on her in-sane show up at Twooga Booga. Thanks for the great afternoon Kathleen and for the video recommendation Rachel!

Untitled, 2013, Flashe, acrylic, and oil on linen, 137.5 x 120″

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Food in Japan

We have been eating really, really well in Japan, thanks one night to Mike-san Abelson-san of Postalco, who shared a lot of critical information with us. For example, about the sanitary face mask situation round here: Since a flu epidemic in the early 20th century, sanitary face masks have been like sunglasses for your face. OK on a date. Worn both to protect oneself from germs and allergies and as a precautionary courtesy to prevent others from obtaining your sickness. Unlike every single other thing here, they are never bedazzled.

Also Nile has been spraining her neck bone major throwing up the peace claws, just like a local. Blast times! Thanks Mike!

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

FIVE

TODAY IS THE FULL MOON! Today is also our shop’s fifth birthday. Mahalo for shopping and for doing all the other things that happen at Gravel & Gold. And a very special thanks to all the ladies and Dustin and Gary who help make it all happen.

I am flying into town this morning and I would also like to especially thank my sister-partner-co-owners Nilie & Lili. We will being drinking champagne and eating cake all day long until we close so that we can go spoil ourselves someplace else. Please come by and party with us! xoxo

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Alice Parrott Working

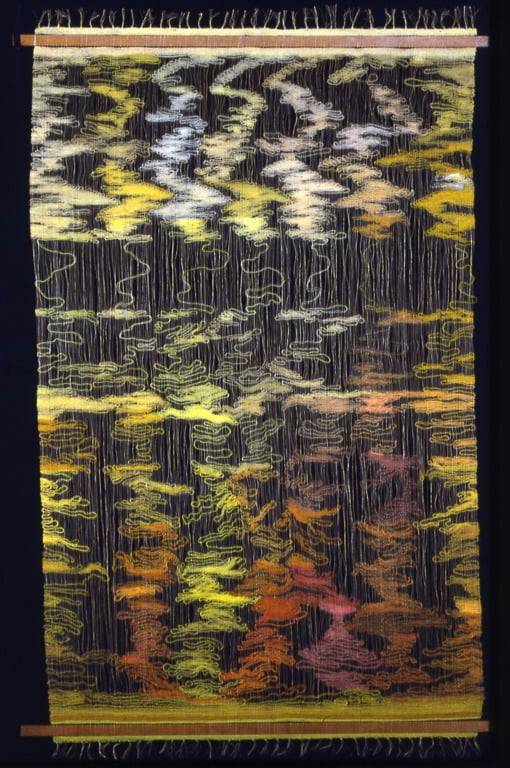

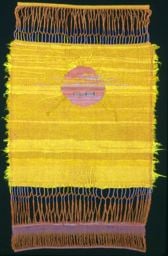

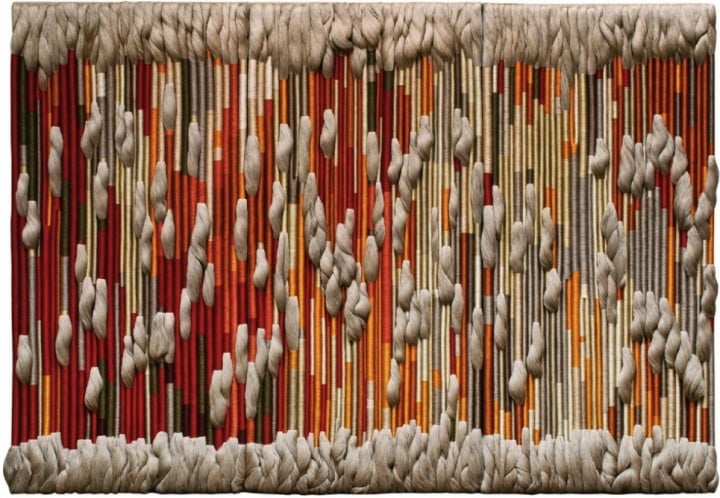

Orange Form, then Fiesta, and Alice at the 1964 New York Worlds Fair.

Alice Kagawa Parrott grew up in Honolulu, the youngest child in a large Japanese family. She studied art at the University of Hawaii and went on to study weaving with Marianne Strengell and ceramics with Maija Grotell at Cranbrook, one of the best art schools anywhere at the time. Her long journey to Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where Cranbrook is located, was her first trip to the mainland.

Here is Alice in the weaving studio at Cranbrook and pottery she was made while a student there from 1952 to 1954.

While she was at Cranbrook, she interviewed to teach at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and lodged that possibility in her mind. After completing her first year, Alice taught in Michigan and had a short stint winding warps for Jack Lenor Larsen in New York over the Christmas holiday.

She enjoyed her time at Cranbrook very much and didn’t have much notion of what do afterward, so she just accepted the New Mexico job offer to teach weaving and ceramics and made her way down South and West. This proved to be a good move.

A killer early hanging from 1969. Then Alice weaving in 1964.

Dry, dusty New Mexico was a completely unfamiliar landscape for this Honolulu girl, but Alice took to it right away. She visited nearby Navaho reservations, where she learned to card and spin yarn, traveled and studied in Mexico. The summer after her first year, she also went up to Pond Farm in Guerneville, California, and did ceramics with the great Marguerite Wildenhain for a month (more on Marguerite to come soon).

Alice met her husband Allen Parrott on a field trip with her students to the International Folk Art Museum in Santa Fe where he was a curator at the time. They were married the day after the semester ended, in 1956.

About three months after the wedding, the couple moved into their home on Canyon Road in Santa Fe, where they lived the rest of her lives. Alice set up a shop out of their living room where she sold her woven fabric and solicited commissions, like the one to make a whole bunch of ponchos for the ushers working at the Santa Fe Opera. These are ponchos I wish I could see whilst enjoying an evening I would like to experience. Also, she had her babies.

Orange Hanging, then Alice with her husband Allen and two of their sons, then Orange Hanging with Circle Motif.

Over the winter of 1971-1972, Alice was an artist-in-residence in Puunene, Maui. While there, she took on a couple large public commissions and she taught workshops to high school teachers from several islands. She also got a nice juice up of the Hawaiian shave ice colors she loved—the great blue sky, flowers, the ocean turquoise—which always show up in her work.

This last shot honors the installation of Maui County Seal at the Maui County Council Chamber, Wailuku, Maui. I would like to take a quiet moment to honor all of these outfits.

Back in Santa Fe, Alice kept teaching, weaving, and radiating happy contentment.

Palaka, then Alice at the loom, then Blue and Green Forms, 1968

Her work was well-admired and she began showing in the mid-1960s. At the same time, she kept her day job working on making wearables and small things like eye-glass cases for her shop, which eventually found it’s own home out of her home. I admire this high-low smartiness.

These two beautiful shots of Alice weaving were taken by Nina Leen for LIFE. And the orange shawl in the middle is one that Alice wove—one of many handwoven items she made available at her dreamboat shop, The Market, in Santa Fe. Droolola….

What I wouldn’t give to be able to shop at this marvelous shop! Just like Sam Maloof and his beloved wife Freda used to do. Alice met Sam at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, where they were both exhibiting with the American Craft Council. Alice had brought these weavings, among others:

And Sam was no fool! After meeting Alice, he’d ask her to make wool shirts for him to wear and fabrics to cover his chairs.

That’s a pile of Alice’s pillows on a sofa Sam built in the 1950’s and kept for himself. Below, Freda is wearing one of Alice’s shirts. Photos via Esoteric Survey.

Milagro

The top image of Alice weaving in an amazing striped muu-muu (always with the stripes!) was taken in Maui in the mid-70s. The detail is from a hanging with wool warp, weft of maguey strings, hand-spun wool, and silk. Published in Craft Horizons,May:June 1964. Via Cathy of California. And the bottom image is Alice in her studio in Santa Fe.

How sparkly is this lady?! It’s been a real delight spending some time digging around for information and pictures of her, always flashing that beautiful smile. There doesn’t seem to be too much information out there about Alice and I for sure would like to know more. Thank goodness (again) for the foresight of the Smithsonian Archive and their brilliant oral history initiative.

Unless otherwise noted/linked, the lion’s share of these images come from a wonderful page set up by Paul Kagawa that has lots more family-style pics of Alice and examples of her work. What a very, very lovely-seeming woman and a true inspiration.

This post originally appeared on the the Gravel & Gold blog.

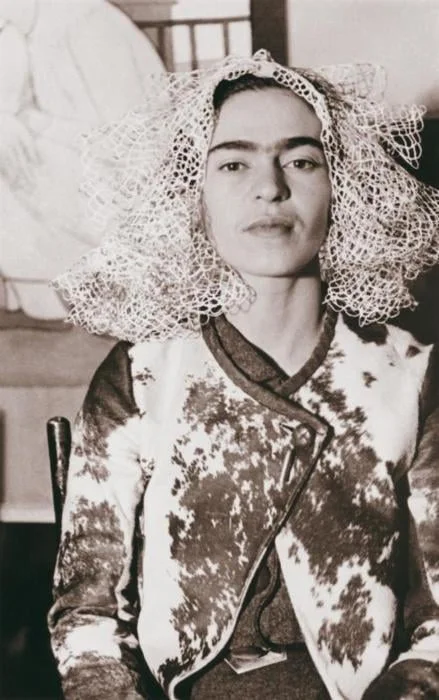

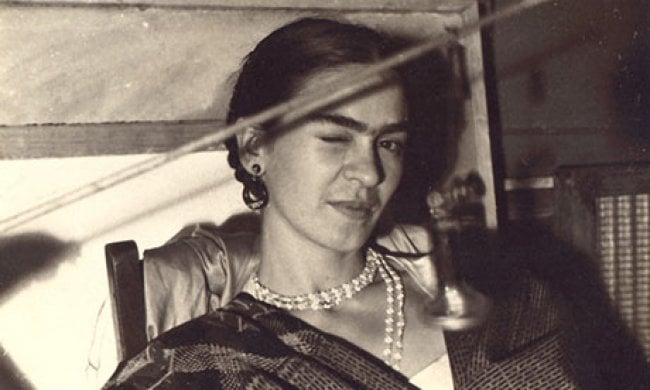

Frida Kahlo Working

Inevitably-

Photo by Lucienne Bloch, 1935

Frida in her Coyoacán studio, 1931.

Nickolas Muray, “Frida Kahlo painting ‘The Two Fridas'” (1939)

When was Frida not working? That’s what I’d like to know. She worked through a great deal of pain, illness, and her recoveries from never-ending surgeries.

By all accounts—her own included—she was a true blue born artist. There are pictures to prove this.

Here she is at 18 with her sisters, photographed by their father Guillermo Kahlo in 1926. Come on—the droopy hankie at 18! This is not a Christmas card sesh; she is working.

Photo by Guillermo Davila, 1929

Just like this is not a smoke break. This cannot be what a smoke break is! Come on! This is working, in that it takes a lot of work to be the one to come up with this whole lewk that the rest of us have been trying to copy for the next century.

Photo by Nickolas Muray, 1941

Also not a smoke break. That is a mustache, though, which has been copied by fewer folks than some of the other elements of this ensemble. And sadly those majority imitators don’t seem to understand that the unibrow and the stache make the lewk, totally!

OK, these two pic might actually be smoke breaks for real. But still, so chic and so beautiful—more beautiful in a way. Pet hawk, hair flowers, uh huh. And who knew cowboy boots looked perfectly wonderful with pajamas? So now let’s copy that too!

Photo by Lucienne Bloch, 1933

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

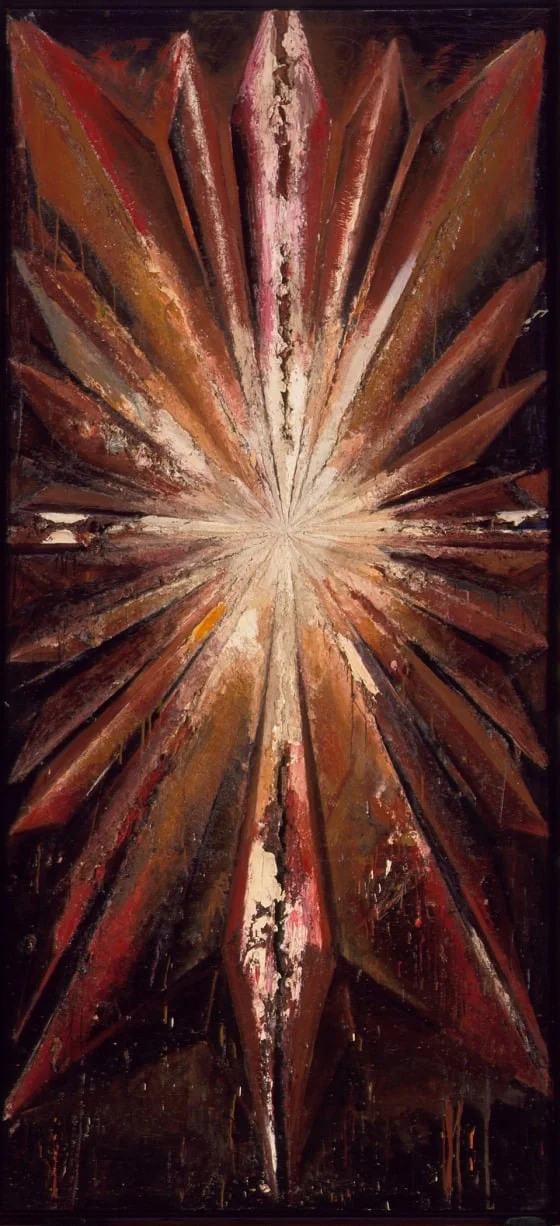

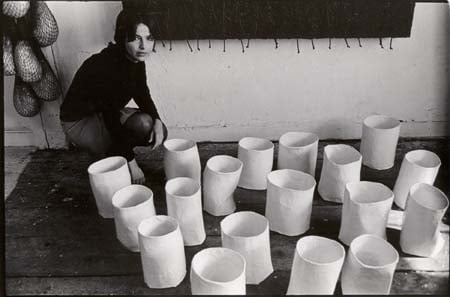

Jay DeFeo Working on The Rose

Jay in her Fillmore Street studio, 1960

There’s still some time yet to catch the Jay DeFeo show at the Whitney if you, like me, missed it at the SFMoMA. I had read about The Rose, but it was even heavier IRL.

Jay was, like, the hottest Beat chick on the San Francisco scene. She co-founded Six Gallery, which hosted Allen Ginsberg’s first reading of Howl in 1955, and was an original member of Bruce Conner’s Rat Bastard Protective Association. Her own work, combining unorthodox materials into hybrid sculptures/drawings/collages/paintings, positioned her among the vanguard of the Abstract Expressionists. Five of her paintings hung alongside groundbreaking work by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella in the important Sixteen Americans show at MoMA in 1959. She was on top!

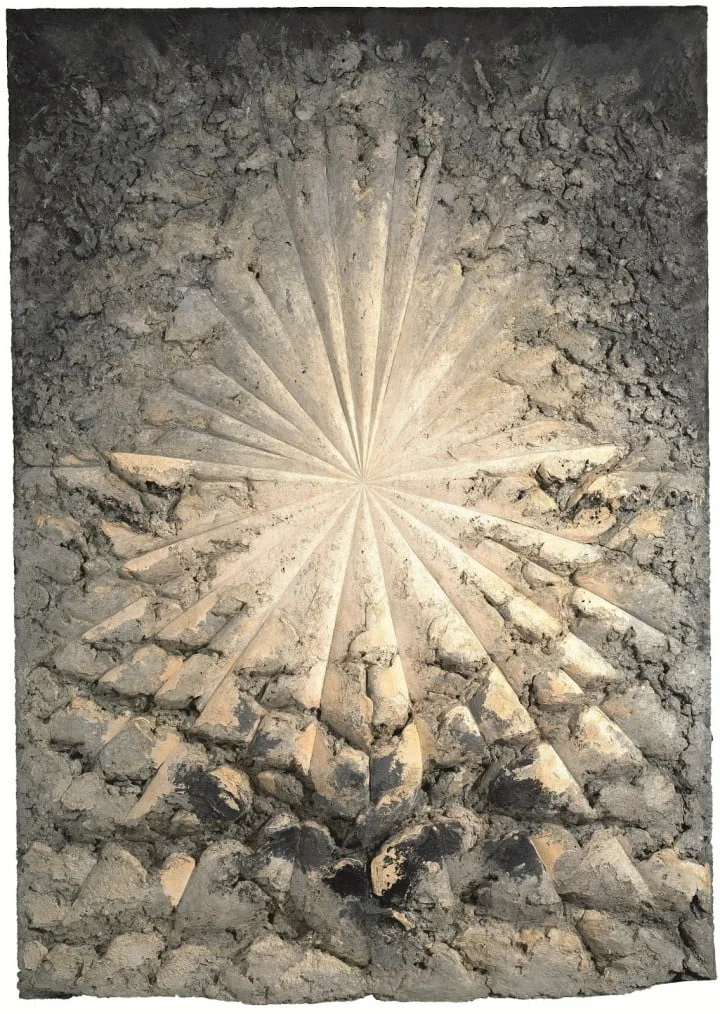

One work that was requested for the MoMA show was a painting Jay had recently begun that was then called Deathrose. It was the concave, darker sister to another painting, The Jewel, that she began at the same time, working on “an idea that had a center to it.” Jay declined to include it in the show, but the MoMA curators knew that she was on to something and included a photo of it in an early stage in the exhibition catalogue.

Here’s Jay at work on The Jewel—

Working on The Jewel at 2322 Fillmore Street, SF CA. 1959. Photos by Jerry Burchard

The Jewel, 1959

Jay took two years to reach a place with The Jewel that pleased her. Deathrose, which was later retitled The White Rose, and finally The Rose, took nearly eight years to complete, from 1958, when she was 29 years old, to 1966. She installed the canvas in a large Victorian bay window and worked up a tremendous surface of oil paint, carving it, adding mica chips, hacking at it, sometimes scraping it back altogether and starting again. There was broken glass in the window and no electricity in her studio, so both she and the painting were totally vulnerable to the damp. She worked by the daylight that steamed in from smaller side windows and against the tightening and loosening of the canvas that occurred as the seasons changed. (“Seasons” is hers. Isn’t it lovely?)

Photo by Burt Glinn, 1960

The painting went through many forms which Jay associated with the different cycles of art history from Primitive, to Classical, Baroque, and back to Classical. There is a wonderful collection of images documenting these changes on The Jay DeFeo Trust website, and here’s some I especially like:

Jay full on with The Rose, then a still from The White Rose, and a nice clear shot of the finished painting by Ben Blackwell.

Jay was made to call a truce with the already legendary painting in 1966 when a rent increase forced her from her studio. By then, The Rose had grown to nearly 12 feet high, up to eight inches think in places, and weighed over 2,300 POUNDS—far too large to fit out the studio door. It took sixteen guys a full day to cut out the window and some of the wall of the building, mount the painting to a larger canvas, and lower it down two stories with a forklift onto a flatbed truck. Bruce Connor documented this in The White Rose (1967), a film I’d like to see.

From San Francisco, the painting was transported to the Pasadena Museum of Art, and Jay went with it to keep working at it for another three months. When she really was done she dropped out to Marin and didn’t work at all for three years….

It was only after The Rose was briefly shown in 1969 at the Pasadena Art Museum, then traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMoMA) the same year, that she began painting again.

Jay with The Rose at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1969.

Unable to find a permanent museum home for her great work, The Rose ended up in a conference room at the San Francisco Art Institute. Conservators there estimated that it would take over 100 years for the thick oil paint to fully dry. In 1974 they applied a protective coating to the surface as that was intended as a temporary measure. The next stages of the planned conservation never happened, and in 1979 a false wall was built in front of the painting. There it remained, out of view, until 1995 when the Whitney Museum acquired it and took on the huge job of restoring it. By then Jay had been gone for six years.

It was all worth it.

Obviously there’s a lot more to this story. You can get started with the Smithsonian archive interview and with the Jay DeFeo Trust, but mostly make sure to see it if you can.

P.S. Jay on the left in 1986, photographed by Christopher Felver. Remind you of a certain hair hero, Wendo? Yeah, that’s “Lee” on the right with “Elliot” in Hannah and Her Sisters, also 1986.

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Mohnton Knitting Mills

The real nudge for our Philly road trip last week was to finally make it to the stripey shirt motherland in rural Pennsylvania, a place I have believed in and described many times over these past five years selling R.P. Miller shirts, but had never seen. I was thrilled to finally meet Gary and Scott Pleam, the current generations of the Hornberger family to run Mohnton Knitting Mills, fresh outta Mohnton, PA.

Our first order of business was to get the pronunciation of their fair town down once and for all: It’s like “Moan-ton” – “Mohan-ton” – Mohnton. Good!

The mill dates back to 1873, when Gary’s great-great grandfather Cyrus Hornberger added a water wheel to a pre-Civil War riffle foundry at 22 Main Street. As Gary put it, “We built this building and the road”, and they’ve got the timber beams to prove it. Aaron Hornberger started a hat factory there in 1878 and later added clothing. Over the years, with the Hornbergers continually at the helm, the mill evolved to specialize in the T-shirts we now sell at the shop. When Scott joined the company in 1997, he became the sixth generation in the family business.

It’s wild to see mounds of stripey shirt fabric and to think that these guys have the power (machines + know-how) to knit it from thread. The mill buys cotton yarn grown in South Carolina and knits the fabric at their factory nearby in Shillington. The fabric is washed and, if necessary, dyed in their Shoemakersville plant, then comes to the Mohnton factory that I visited to be cut and sewn into garments and shipped out.

This is Beverly. She’s worked at the mill for 46 years. She did have one other job before this one—in high school, she worked a switchboard for two days, earning $1 per day. Otherwise, she has always worked at Mohnton Knitting Mills. And man, could she pop out some neck binding and attach some tags. Zow! She was fast!

When Beverly began working, the mill was at the top of its game with over 100 employees. Sadly, despite the great quality and completely reasonable price of their products, the mill has not been immune to the hardships of U.S. manufacturing. They are now down to just 20 employees and sell a hefty chunk of their T-shirts to Japanese customers who seem to understand what it is they’re getting. We understand too! And we want to buy and sell zillions of these shirts and keep the Hornbergers in business!

Here’s Scott pointing out his relatives in an old shot of workers at the mill.

Thanks so much, Gary and Scott! I hope to come back and visit you guys again soon! And next time, I’m bringing Lisa, Nile, Holly, Tessa, Em, Rachel, Emmy, Abby, and all the other girls!

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

I built this sanctuary to be inhabited by my ideas & my fantasies in Philly

Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens: I am in it (proposed “author photograph” for proposed “journalistic career” by Alisa).

A few years ago, Joan Gardner advised that I learn about Isaiah Zagar’s work by passing along his son Jeremiah’s beautiful and intense film, In A Dream. To see the Magic Garden in real life feels the same way. Thank you, Joan.

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Three for Nilecat in Philly

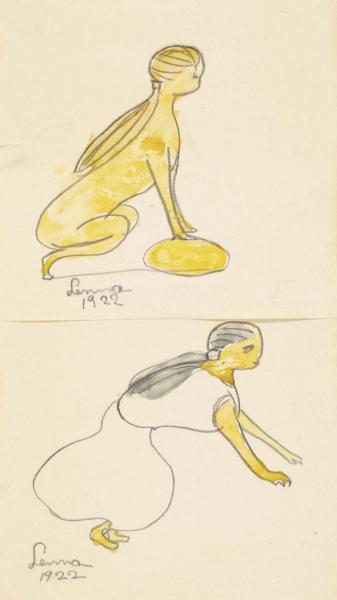

Two Figures-Sphinx

Lenna Glackens

1922

How come people only medium suggest going to The Barnes Collection? The Barnes is fantastic! Even with all the blowsy Renoirs, even on a Friday night when they have a guest African dance-a-long performance blasting from the atrium, it’s still fantastic! Part of the fun here is imagining what this fellow Dr. Albert C. Barnes was thinking when he collected all these paintings, sculptures, ancient artifacts, early American furniture, Navaho chief’s blankets, late 18th century iron door hinges, and other things he was into and then assembled them as he did, all together. I also found myself anxiously thinking of what all the anxious conservators were thinking as they measured the dimensions of each room of his home and his arrangements before transferring the collection and replicating the whole deal in the city down to one-sixteenth of an inch. That job and these three images reminded me of my friend Nile.

Two sweet drawings by Lenna Glackens (here’s the other one) especially got me thinking about this oddball Barnes. I like them and I really like that he included them in the mix along with many painting and drawings by her father, William James Glackens, who helped Barnes form the collection. From one oddball to another, the clothing on, clothing off deal reminds me of Goya’s naked vs. clothes Mayas and the bottom figure reminds me of Wyeth’s Christina’s World. Lenna was 9 when she drew these minxy sphinxes.

“A Montrouge”–Rosa La Rouge

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

1886–1887

Also a Wyeth woman foreshadow. This one, Helga.

Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate

Hans von Kulmbach

c. 1510–1520

According to Chelidonius: “Overjoyed Anne threw herself into the arms of her husband; together they rejoiced about the honour that was to be granted them in the form of a child. For they knew from the heavenly messenger that the child would be a Queen, powerful on heaven and on earth”. I gather that lots of expectant parents feel this way, and so did the Virgin Mary’s folks. To me though, Anne has got that labor look. Maybe she was one of those mysterious mamas who didn’t realize she was pregnant til her water broke and she’s having to break the news and deliver her baby all at once. But what do I know?!

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Apprentice Swatchbooks in Philly

Blessed be The Fabric Workshop and its apprenticeship programs.

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Lenore Tawney Working

Night Bird (1958) and Lenore in her South Street NYC studio working on Vespers, 1961. Photo by Ferdinand Boesch. Then Lenore at work on a tapestry circa 1966. Photo by Nina Leen.

Lenore in her NYC studio, 1958. Photo by David Attie.

The Bride Has Entered (1982) and Lenore at work on a tapestry. Photo by Nina Leen, published in LIFE, July 29, 1966. Then Yellows (1958) and Yousuf Karsh’s portrait of Lenore, 1959.

Union of Water and Fire (1974), photo by Tom Grotta. Then, Union of Water and Fire II (1964) and Lenore’s first solo show at the Elaine Benson Gallery in Bridgehampton NY in 1967. Eye spy Noguchi!

Bound Man (1957), photo by Ed Watkins. Then another photo of Lenore by Nina Leen, this one from 1969. Then a picture of something I know about but I don’t know who captured it.

“I’m not just patiently doing it,” she said of such work. “It’s done with devotion.”

Waters Above the Firmament (1976) and Lenore in her NYC studio with Dove (1974). Photo by Clayton Price. Then a view ofLenore in her studio.

Verdi (1967) then Four-Armed Cloud (1979), pictured with dancer Andy de Groat at the New Jersey State Museum. Then Discours Historique (1966), photo by George Erml.

Lenore working in 1979. Photo by George Erml. Then Lenore’s loft in 1994 as photographed by William Seitz. And a blissed out working Lenore dressed to match her loom set up.

Lenore Tawney, a great and tough beauty, lived to see 100 years. She studied sculpture with Alexander Archipenko, drawing with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and weaving with Marli Ehrman at the Art Institute of Chicago. Later she studied tapestry with the Finnish weaver Martta Taipale at Penland School of Crafts, where the weaving studio is heaven on earth. After some personal turmoil and travels, she went to New York and stayed working there for the rest of her day, breaking art rules. “I left Chicago,” she later wrote, “to seek a barer life, closer to reality, without all the things that clutter and fill our lives. The truest thing in my life was my work. I wanted my life to be as true. I almost gave up my life for my work, seeking a life of the spirit.” Sound familiar? She and Agnes Martin were close.

There is a really nice corral of images at the American Craft Council site, along with an article published in American Craft Magazine, in 2008, called “Lenore Tawney: Spiritual Revolutionary.” I wish I could meet Lenore.

“I’m following the path of the heart. I don’t know where the path is going.”

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Sheila Hicks Working

Sheila holding Éventail in 1989 in Cour de Rohan, Paris. Photo by Cristobal Zañartu. Then Convergence I (2001) and Linen Lean-To (1967-68).

M’hamid (1970)

Sheila in Guerrero, Mexico, 1964 from Weaving As Metaphor, the book I would most like to purchase but am too intimidated by the out of print price. Learning to Weave in Taxco, Mexico (c. 1960) and working on Solferino Tacubaya in Taxco el Viejo, Guerrero, Mexico, 1960-61.

Blue Book Blocks (2008)

Wil Bertheux (1973), photo by Bastiaan van den Berg.

La Memoire (1972) as it was originally installed at IBM headquarters in Paris.

Self portrait, 1961

Proust Visits the Brooding Winter Tree (1999), Lianes Nantaises (1973), Wow Bush / Turmoil in Full Bloom (1980), The Silk Rainforest (1975), Tahoe Wall (1970), and a study for Fugue Rothschild Bank Headquarters, Paris, 1969. Zaaaaannnnnngggggg -Holly Samuelsen

Sheila at Yale. Photographed by Ernest Boyer in May, 1959.

Grand Prayer Rug (1966), The Double Prayer Rug (1970), and a portrait of Sheila by Martine Franck, 1971.

At Sheila’s Paris studio and Wrapped and Coiled Traveller (2009)

Photo of Sheila by Ryan Collerd for The New York Times (also a wonderful article).

I’m heading down to Philadelphia today, and all my life, Philadelphia will mostly just mean Sheila Hicks, ’cause I was one of the lucky ones to see her big show at the ICA a couple years ago. It completely spun me out. Sheila is our great head honcho, the top fiber arts dog of all time. She studied at Yale with Josef Albers in the mid-1950’s, then went down to learn weaving in Mexico. Since then she’s been based in New York and Paris, basically laying down the category of fiber arts both small and largescale, for both industrial use and for the purpose of just mind-melting wizardry.

One thing I noticed when I was at the show was how many of her pieces were commissioned for corporate lobbies, like at IBM, and corporate spaces, like a bank in Mexico City, an insurance company in Milwaukee, and the poshest Air France Boeing 747 ever. This got me thinking: 1. I often skip looking at woven panels and carpeting in public spaces because BART is so gross, but sometimes it’s magnificent and I should pay more attention (and I do). 2. If big corporations are the only guys with enough cash and foresight to commission crazy big fiber installations like hers, then suddenly I’m all for big corporations.

There is much to read and learn about Sheila. Check out Sikkema Jenkins & Co., her gallery in New York, for even more images of her work. The Smithsonian has also done an oral history with her and there are many nice books out—Sheila Hicks: 50 Years is one we carry at the shop.

Sheila Hicks, photographed by Giulia Noni.

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Claire Zeisler Working

Still from a film by Patricia Erens I’d like to watch, Claire Zeisler: Fiber Artist (1979), then Symbolic Poncho (1971).

A polaroid from the Smithsonian archive, then Coil III- A Celebration (1977).

Claire’s got her back to us and her assistant all tied up. Photos by Jonas Dovydenas.

Stela II, Red Preview (1969), unknown title, Tri-color Arch (1983-84), Free Standing Yellow (1968), Private Affair I (1986), Blue Vision (1981), Totem III

Claire with Dimensional Fiber, c. 1980, a sketch for Hirise on graph paper, ca. 1983, and two study samples (1950).

Breakwater (1968) and Claire putting pegboard to excellent use in her studio.

Red Forest II (1971) in it’s full 38 foot long majesty and a detail, then Coil Series I (1977) (I’m with you Cathy.)

From Beyond Craft: The Art of Fabric by Mildred Constantine and Jack Lenor Larsen, 1972.

Listen to wonderful Claire talk about the challenge of free-standing fiber sculptures!

And read more from her Smithsonian oral history interview. Also, many of the images of these works come from the Art Institute of Chicago archive. Check that out too!

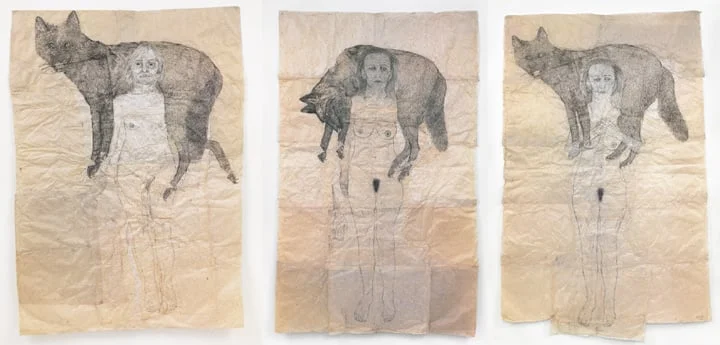

Kiki Smith Working

Photo by Chris Sanders (2008), Worm (1992), Valerie Hammond’s photo of Kiki’s back (2012), Eldridge Street Synagogue rose window (2010)

Photo by Lina Bertucci (1993)

Eyes and hands scarf on rayon (1982) and photo of Kiki by Peter Sumner Walton Bellamy (1984).

Tony Smith’s witchy daughters (Seton, Bebe, Kiki on the right), Night Vision (2011) and Tom Warren, Kiki Smith (1981)

Free Fall (1994)

Born (2002), bottom photo of Kiki by Chris Sanders.

Carrier (2001)

Working on etching plate for Ginzer at Harlan & Weaver, NY, Photo by Gavin Bond (2000), Kourai (2005), and at Mayer’sche Hofkunstanstalt (2007).

Kiki Smith, obvi an auntie, was also born in Germany like Eva Hesse, but really she is the boss of the Lower East Side (See:This 1994 profile. “I was happy at Fawbush, but my astrologer said I had to make a change”). See also: Tony Smith /Seton Smith. Lili—ink like this, yeah?

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Eva Hesse Working

Eva Hesse then in her Bowery studio, NYC (1968)

This group- Henry Groskinsky for LIFE (1969)

Eva Hesse in her Kettwig Studio, Germany 1964 and 1965

Sans II (1968)

Repetition Nineteen III (1968)

Top is Gretchen Lambert, Eva Hesse in her Bowery studio (1965) then Ingeminate (1965) and Hess with it.

At an opening in 1965, then Ascension (1967).

Untitled or Not Yet (1966)

If you’ve made it this far without cracking your heart open like a watermelon and you need to obsess some more about Eva, check out her archive at Oberlin College. That’ll do the trick. And then this sweet letter from Sol to finish you off.

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.

Agnes Martin Working

Milk River (1963)

Untitled #6 (1980)

Diane Arbus, Agnes Martin, N.Y.C. (1966)

Falling Blue (1963

Untitled (1960)

Untitled (1964)

Steve Northrup, Agnes Martin, Taos (1977)

Faraway Love (1999)

Thanks for a wonderful weekend, Jana. xoxo

Dia:Beacon

This post originally appeared on the Gravel & Gold blog.